When people are talking about the widespread uprising in Myanmar nowadays against the junta, so many people try to draw parallels with some kinds of other dictatorships. Some think of South Korea's military junta. Some think about the reformed communist dictatorships in Vietnam and China. Some look at the old Indonesian, Filipino juntas or current Thai monarcho-junta. There are even comparisons to the strongman rule based on monarchial power like Cambodia, or isolated outcast North Korea. Well, yeah, it is not wrong to compare, but there is a major problem. And we need to address it immediately.

The root

For most of its history since independence from Britain in 1948, Myanmar, or also known as Burma, has always been beset with military coups and violence, as well as government's mismanagement. And this is what led to the downfall of Myanmar from grace.

In the history of ancient and medieval Burma, the country produced three major empires, the two latter, Taungoo and Konbaung, were nightmares to many of its neighbours and menaces for China. During the era of British Empire, Myanmar was the richest country after the Philippines in Southeast Asia, and was one of Asia's best performed. Unsurprisingly, Myanmar was given as a jewelled crown of the Imperial Britain, and had everything for the other Asians to dream for.

But it came with a price. To make Burma, the country's name given by the colonizers, rich, the British colonial administration wasn't hesitant to empower the ethnic minorities at the expense of the Bamar majority. The British government made up its colonial army exclusively from the bases of the loyalists, such as the Karens and Kachins who converted to Christianity thanked for American and British missionaries, and the Indians who migrated with encouragement from the British governours. The resources were also ruthlessly exploited by the British for their economic clouts. Thus the resentment rose and nationalism swept throughout the Bamars. The Burma Independence Army, founded by General Aung San, now Myanmar's national hero, got the xenophobic root within.

During World War II, the Bamars supported Japan and the Burma Independence Army renamed the Burma National Army. Any hardcore Bamars loved this. But not the minorities, who used to live in luxury provided by the British, felt threatened. Thousands of Karens, Kachins, Rohingyas, Chins had lost their lives due to joint Japanese-Bamar oppression. This, however, greatly broke the heart of Aung San, and he became more pacifist in nature, seeing how diverse Burma was, still now.

Aung San's idea of a multinational democracy for Burma was viewed with suspicion by the other members of the Burmese nationalists, as they carried the supremacist view. So when Aung San signed the Panglong Agreement in February 1947, the General was assassinated in June and his promise of a federal democracy was never honoured. Burma proclaimed independence in January 1948, but the issue of Panglong Agreement wasn't brought back and became a cause of tension between different ethnic groups to the Bamar majority.

|

| The Burma Independence Army in 1942. |

Well, the Burma National Army also effectively became the Tatmadaw, the modern army of Myanmar today. The Tatmadaw, in Burmese, means "Armed Forces". The military of Myanmar was actually even older than that of modern Burma statehood, and Aung San had ingrained into the military the motto "One blood, one voice, one command". This simply examines the mentality of Burmese military, something that had been rooted in its long militaristic past.

Unusual totalitarianism

When Burma got independence, strained relations between the Bamars and minorities pushed the nation into a long-running insurgency. Still, at the time, Burma was a representative democracy, modelled after British Westminster, and the issue had been several times debated in order to avoid further bloodshed. Yet, the civilian leaders of Burma showed no sign of conceding for the greater, still persuaded for a centralised statehood instead of a federal democracy. On one hand, several political groups disgusted by the slow process also entered into the insurgent mode, notably the communists and the Kuomintang.

The Tatmadaw played a major role in fighting these insurgencies, but it didn't become prominent immediately until 1958, when the civilian government was in crisis due to ongoing political infighting. To solve this, then Prime Minister U Nu requested military chief Ne Win to temporarily form a joint government. Ne Win nodded, and for the next two years, Burma was under a quasi-democratic government. The military promised to give back power to the civilian aftermath, which they did, when Burma entered the 1960 election. But this would prove to be a false flag; two years after the general election, Ne Win seized power in a coup d'etat, justifying by the possibility of disintegration of the state.

Two short years of experience with some form of quasi-democratic government gave Ne Win the necessary knowledge on how to run a government - with military clothing. After capturing power, Ne Win assured there would be no opposition groups by either banning, exiling and torturing dissidents, except for his party, Burma Socialist Programme Party (BSPP). Under his rule from 1962 to 1988, Burma, by then one of Asia's jewel, fell into despair. Ne Win didn't align Burma with either the United States or the Soviet Union, two superpowers during the Cold War, but his policies amply resembled the Soviet-based centralisation program. Still, Burma, a non-aligned nation at the time, also included a number of articles that later ensured the privileges of the military, such as Buddhist nationalism and affiliated conglomerates. The Burmese military also violently cracked down 1974 protests and more roughly the 1988 Uprising.

|

| Tatmadaw troops in 1988 uprising. |

The 1988 uprising in Burma started in a very unusual fashion. Although there had been protests against military corruption and economic illness, Ne Win's decision, influenced by an astrologer, to withdraw banknotes that did not add into the number 9, considered by himself lucky number, triggered widespread demonstration. Ne Win, in the final speech as leader of the BSPP, intimidated protesters that,

The army has no tradition of shooting in the air. It shoots straight to kill.

He delivered the promise he had spoken out. His henchmen, Sein Lwin and Saw Maung orchestrated the massacre of 3.000 Burmese student protesters, before "removing" Ne Win.

The junta renamed itself "State Law and Order Restoration Council" (in 1997 they changed again as "State Peace and Development Council") and renamed the country "Myanmar" in 1989, the name that has been spoken in Burmese language. Two years later, they agreed to hold an election, under the presumption of an easy military victory. The result was reversed: the National League for Democracy, led by future Nobel laureate, Aung San Suu Kyi, won by 80% of the vote. The junta refused to acknowledge the defeat, imprisoned Suu Kyi and suppressed opposers. It took two decades before the military finally relinquished, by part, its role in the government in 2010, but not before they wrote the constitution of 2008 as a prelude.

The abnormal of this junta in Myanmar is enormous. It was, still left-wing by root, because it worked the same way with some other communist, militarized states and revolutionary ideals, but incorporated a strongly right-wing dogma like Buddhist nationalism, Bamar racial superiority and militant conservatism. It's stayed in complete isolation and maintained a secretive profile. It found more similarities with Russia and later China, but did not fully listen to either of them. The Generals were and are very religious, they believe in numerology and the existence of haunted spirits, stars' powers, etc. They often consult witches and astrologers.

It was no surprise that, with superstitious Generals, the junta decided to move the capital from Yangon to a newly-constructed city in the centre, Naypyidaw. And they moved in coincidence to an astrologer who spoke to them the number 11. At 11 o'clock, with 1.100 military vehicles, on 26 March 2006, building a massive 20-line highway.

Unsurprisingly, the power of stars, the numbers, the supernatural feelings, etc was even more than the people's will. All is for the belief. Unrealistic thought was more of a priority. It stands still today. This explains the bloodthirst substance of the Tatmadaw unchanged throughout times.

In the end, the Burmese junta is leaned to left-wing, but not a kind of left-wing revolutionary one. It is rather a reactionary mode. Totalitarianism forms the core of the Tatmadaw command. It didn't come to power by choice, but rather by chance, and slowly got used to it and happily enjoyed it despite the whole nation suffers.

Comparison to other Asian dictatorships?

It's hard to believe which dictatorships in Asia sound similar to Myanmar. Probably, it appears very distinctive North Korean by style. But the Generals at least ceded power, well, by half, for a quasi military-based democracy, only to remove it again in 2021 for a pseudo National Emergency Law.

The closest to compare for the Myanmar junta is Thai junta, but the difference is also huge. And this is not a secret. Thailand has been beset with the same state of political instability, but the Thai Armed Forces have to rely heavily on the support of the Chakri monarchy to survive. Previous late King of Thailand, Bhumibol Adulyadej, or Rama IX, was a staunch reformist and a King who, even after passing away in 2016, still loved by the rest of the population for his kindness, devotion to the country's development and his resentment to the military corruption. Moreover, under Rama IX, Thailand entered a new economic boom from 1950s and became relatively wealthy by 1990s. There were also accusations against the late King, such as his involvement in the Thammasat University massacre in fear of communism, yet it was the same King who later condemned the military role and voiced his regret. Today, the Thai military still involved in politics, this time they have an easier King to manipulate, Rama X Vajiralongkorn (also mocked as Harem King for his sexual habit). But Thai junta appeared to be more lenient, cautious and less lethal, fearful of widespread reprisals. That is also contributed to the fact that the Thai economy is one of Asia's largest, most energetic, and friendly relations with the United States and China. Thai people are also more educated, and while they have protested, the Thais largely stand in a resilient and civilised manner.

|

| The Thai military leadership is often cited as similar to Burmese counterparts. |

By contrast, Myanmar has just opened to the world for a short-lived 10 years span. The economy of Myanmar is 40 times behind Thailand, and the military of Myanmar is also renowned for being brutal and merciless. The Burmese protesters were initially resilient and peaceful, but the crackdown made them more violent in response. The junta of Myanmar's policies have also been, despite difficulties, pro-Chinese, making them less reliable for Western partners, and to an extent, Japanese, Indian and South Korean firms. The geographical location of Myanmar is also important as well, for several countries, making Myanmar likely to be messed.

There are also comparisons to the other juntas, such as the once South Korean, Indonesian and Filipino ones. But even the comparison is also very outdated, due to significant differences. This was best seen by the junta governments in both South Korea, Indonesia, Taiwan and the Philippines had some similarities: very autocratic, conservative but right-wing. In addition, the dictatorships of both four nations, in contrast with Myanmar, supported crony capitalist economies as the main way to drive, though the Philippines appeared less successful. But the most important thing that made South Korean, Indonesian, Taiwanese and Filipino military governments impossible to be drawn in line with the Burmese equivalent, was the acceptance of transformation to democracy. Chun Doo-hwan of South Korea, Suharto of Indonesia, Lee Teng-hui of Taiwan and Ferdinand Marcos of the Philippines were no saints, but when they realised that the power could no longer in their hands, voluntarily gave up in face of popular opposition. This was totally absent in the Burmese case.

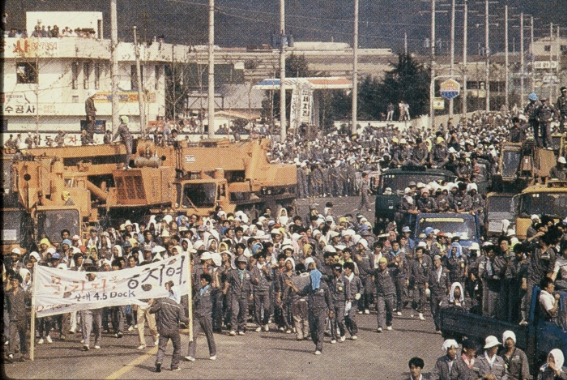

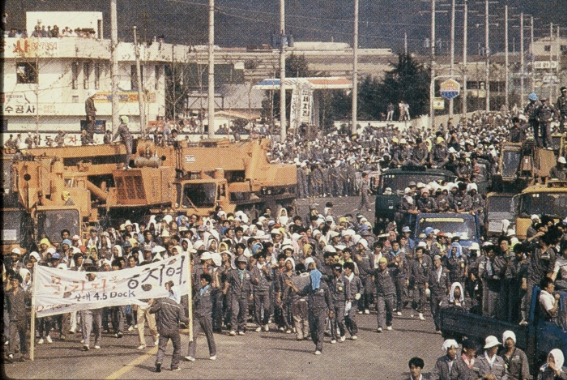

|

| South Korean workers protesting against military rule in 1988. |

Then, we sought comparison with some fellow left-wing totalitarian regimes like Vietnam and China. It appears closer than these dictatorships mentioned above, but it doesn't mean they are the same. Because they had nothing in common outside some forms of dictatorships.

True, both Vietnam and China were dictatorships, still are. Yet, both two countries are willing to engage with the international community, so they agreed to embrace economic reforms, in China in 1978 and Vietnam in 1986 - it was worth a try and it is. They've managed to maintain power and suppressing the dissidents, but at the same time, they accepted capitalist governance to boost trades and economic competitiveness. So in some aspects, China and Vietnam stay totalitarian but free and liberal enough at the line that drawn by so that the regime could prevail while the money, investment, trade, FDI, etc, keep flooding. More oddly, Vietnam and China are parts of the Sinosphere (Chinese cultural sphere zone), this cultural world is emphasised throughout the idea of a strong, powerful centralised government, and they care little about which patterns the people choose, as long as it proves healthy. South Korea, Taiwan and Japan have undergone modernisation successfully under a string of totalitarian governments before democratisation.

|

| A fellow Southeast Asian nation, Vietnam learned reforms from China and embarked on a successful program of reorganising the economy to become a rising dragon despite maintaining totalitarian rule. |

Unfortunately, Myanmar belongs to the Indian sphere of culture, meaning that they have little in common with Vietnam and China. The shape of Myanmar's governance is based on the mandala, where the central power lies in the wealthiest city. Already with this government, it prevented Myanmar from effectively democratised as the power lies in a central city rather than on the whole nation. For decades, Myanmar struggled to make itself stable; but so were Vietnam and China. Yet, while China and Vietnam stabilised and prospered since 1990s, Myanmar stayed behind. Even after 2011 reforms, nothing concluded on Myanmar's path to development, the military that once ruled Burma with iron-fist refused to step down.

Moreover, if we specifically talk about Vietnam only due to ASEAN membership, actually Vietnam has the ball, unlike Myanmar. Even though Vietnam is a communist dictatorship, it has learned to not rely on China, a legacy of the Vietnamese-Cambodian War, 1979 war and subsequent 11 years of border war and other short invasions (you may also count on over 2,000 years of grievances between two nations). Even now Vietnamese government still has a strong sense of disdain against China and doesn't like to follow Beijing's censorship, by breaking its deadlock and work with the United States and Washington's allies. The best example was Vietnam permitting a Taiwanese government plane to land in Hanoi during the 2006 APEC Summit displaying the flag of Taiwan (Republic of China), something that was never done before in a communist country nor even a nation lacking formal relations with Taiwan (Taiwan and Vietnam have no official relations due to One-China policy), this triggered Beijing's protests. During COVID-19 pandemic, Vietnamese government secretly authorised a hacker group to attack Chinese government's websites to gather Beijing's cover-up attempts and was eager to produce its own vaccines (with supports from South Korean, Swedish, Indian and American firms) rather than buying from China's Sinovac and Sinopharm. Not to mention Vietnam has never bought any Chinese weapons since the end of the border war in 1990. On another hand, Myanmar, despite similar anti-Chinese sentiment knowing China did lots of harm to her country, by supplying various ethnic rebels, but instead of openly trying to confront China for a fair share, chooses silent and buys Chinese arms. Likewise, many Burmese are very naive in the first place, when China stood side-by-side defending the military of Myanmar when it conducted ethnic genocide, it was seen as a favourable action, a pro-Burmese. Only by 2021 protest that finally Burmese people became more resentful of China when they saw how China manipulated them.

In the end, we think of North Korea - the Hermit Kingdom. North Korea has actually had the most coincidences with Myanmar: militarised societies, feeling insecure with China at the border and paranoid leaderships. The Generals of both nations, in particular the Kim dynasty and the Tatmadaw's reign of terrors, were deeply unseated and always sceptical. They governed their nation in complete isolation, building grandeur palaces for themselves, making decrees there. However, the North Korean regime skillfully put the whole population under its hand, whereas the Tatmadaw didn't have the same achievement, with only a few loyalists bother.

Anyway, North Korea and Myanmar share unique relations between, too. North Korea and Myanmar back then used to be hostile when North Korean agents conducted an assassination on South Korean delegation in 1983, but later supported each other after 1988, and Myanmar tried to buy nuclear technology from North Korea for its nuke ambitions. It was never materialised. Still, even when Myanmar opened up, the military's illicit trade with North Korea remains.

To be simple, North Korea looks as if Myanmar going to be the same. And probably North Korea has the highest degree of likeness.

An uncertain future

Myanmar's future is uncertain. Given the circumstance, Myanmar is likely to descend into further chaos, as the protesters have shown their fierce determination. The military has also shown no sign of backing down either, it is prompting more charges, arresting and torturing members of the National League for Democracy (NLD), curbing media freedom, as well as placing notorious battalions into the main cities cracking down on people opposing its rule. The Tatmadaw has also had little concerns about international sanctions because they have extensive networks of economic holdings across the country and being stockpiled with Chinese and other Asian investments, Beijing is Myanmar's biggest trade partner and the second-largest investor and ASEAN non-interference principle.

At the same time, arguments about how to handle it overshadowed the deteriorating condition in Myanmar. The West, led by the United States, has taken harsh tones and considered it a coup d'etat, imposed sanctions alongside Britain and the EU. But China referred to it as a "cabinet reshuffle". ASEAN countries like Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines try to take initiatives, but nations that have no credibility of democracy like Vietnam, Singapore and Thailand accused of blackmailing in favour of the junta. India, a member of the QUAD alongside Australia, Japan and the United States, has already been condemned for stay deaf, is now planning to deport refugees from Myanmar in spite of security concern. Some nations like Russia and Israel are allies of Myanmar junta and unlikely to step out. Syria 2.0 is looming as nobody knows what is waiting for Myanmar in the future.

DW just made a report about Myanmar's uprising, and the Germans drew a blasé article: "the whole revolution in Myanmar only has its people to fight for their own". I don't remember which article was, but this reminds us of a translucent fact going on: Myanmar is not safe and is not attracting enough global support. And we are walking in a gunpower that is likely to explode and can become a global crisis. The world already has instabilities with regard to Syria, Yemen and Afghanistan; just recently they managed to unite various factions in Libya for a fragile peace. If a similar story breaks out in Myanmar, few can imagine what's going next.

It's up to the world to do something when facing such a merciless, violent junta that has reigned Myanmar for half of a century and again in 2021. Yet we're again going to the same, predictable decisions, to fight against an unpredictable junta.

Comments

Post a Comment