The intertwined tragedy of neighbours: how Colombia and Peru became entangled in an endless problem?

Speaking about South America, I don't have so much knowledge outside sharing similar Spanish heritage, beautiful women and passionate football fans. Yet, when going to the Latin American world, I always have a fascinating question: why is the region so uniquely difficult to characterise?

Well, my favourite country in South America has to be Chile, or maybe Uruguay. I'd say Brazil and Argentina when it comes to football. I admire the Chileans for their eagerness to progress despite difficulties to maintain a healthy, though far from a perfect society. I like the Uruguayans because of their progressiveness that allowed Uruguay to become one of the wealthiest. I can also add Ecuador and Bolivia, because of Leo Rojas, mountainous music of freedom and their native cultures untouched by time.

But in the mind of a Vietnamese person, I'd expect more to speak about two South American countries that are definitely worth making the world feel sympathy. It has to be Colombia and Peru - the duo of South America, with passions for their stories to go.

A difficult past

From Inca to Spain

Peru and Colombia were bounded to be neighbours.

In the past, Peru was the centre of the famed Inca Empire, the largest pre-Columbian empire that expanded from the modern day's Colombian Andes to northern Chile and Argentina, occupying a large sea coast as well as creating a distinct culture that bound them into a common sense of common: the Quechua, Aymara and other indigenous people emerged. It was the people from the Andes Mountains that carried out lavish architectures and social organisations to these South America Pacific coastal tribes. Nonetheless, differences existed. The land of today's Colombia was not just only for Incans, but also had varieties of native nations like Chibchan nations, most renowned being the Muisca statehood, albeit strongly influenced by the Incans.

It proved no lasting forever. The Spanish conquistadors successfully landed on the coast of Panama, using it to march into the Muisca nations, began the conquest of South America. With only Portugal competing against, Spain managed to annex most of South America, only leaving a vast territory that would become future Brazil for the Portuguese. Rodrigo de Bastidas, encouraged by Alonso de Ojeda, established the first city in South America, called Santa Marta, which lies in coastal Colombia to the Caribbean. It still exists today.

After destroying Muisca, the Spaniards headed for Inca, using the roadmap navigated from Colombia to extend its empire. Francisco Pizarro, an associate to Alonso de Ojeda and friend of Hernán Cortés, founded the first colony in Peru, called Piura. Peru was also where the first university of the new world was born. Later on, the Spanish King designated the Viceroyalty of Peru and Viceroyalty of New Granada as economic hubs. These viceroyalties were exploited with no mercy, where the Spanish conquistadors brought into them millions of African slaves, some as far as from Madagascar, to settle; a successful missionary program converted the majority of Muslim African slaves to become devout Catholics. The Spaniards further exonerated the racial marriage between Spanish settlers with the native Indians of South America to create a sustainable system and produce a string of loyalists to the Spanish government, creating the first Mestizos in the new world. Native Incans tried for insurrection, most famous being Túpac Amaru, ultimately met their fates getting crushed and its leaders decapitated. The economy of Spain began to decline in the 18th century, two centuries after its golden age, but still formidable. Spain then looked for administrative and political reforms, as well as economic liberalisation.

|

| From 15th to 18th century, Spanish galleons frequently moved between the Americas to Iberia, symbolising the wealth and prosperity of the Spanish Empire. |

Spanish rule didn't last long. When Spain suffered upheavals in the 19th century, being occupied by Napoleonic France, the local population revolted against Napoleonic Spain, hoping to get equal treatments from Madrid, so initially, it joined as part of anti-Napoleon resistance. But the eventual King of Spain at the time, Ferdinand VII, failed to meet the demands of the mass. Angered, the uprising against Napoleon became a war of liberty against Spanish despotism. Viceroyalties of Peru and New Granada was hit hardest, because of being the major economic providers in South America. Supported by the United States' successful uprising against Britain a century earlier (1770s for exact), people of Peru and New Granada took arms and rebelled.

Nonetheless, Peru was a strong royalist ground. While the Spaniards might have lost control over New Granada, Peru was never far from being touched - it used the Napoleonic crisis to seize Upper Peru, a land that would go on becoming Bolivia. It took more than a decade before José de San Martín and Simón Bolívar, the latter hailed from New Granada, to coordinate before finally entering Peru. The coordination lacked an immediate timeline, but when the Chileans joined forces with the Argentine San Martín, Peru was finally taken down in 1825, the Argentine also declared himself President of Peru. Throughout this time, however, New Granada provided a new essence of patriotism, called the junta movement (the junta was a patriotic municipal revolutionary council against a foreign invader, first issued during the Napoleonic war in Spain, to differ from the junta as a military dictatorship). The Peruvians were enthusiastic, adopted it immediately. Figures like Antonio de Zela, Mariano Melgar and Mateo Pumacahua represented the hope what many Peruvians had felt.

An era of state-building

Yet when Peru and New Granada were born from the ashes of Spain, the situation started to break. New Granada was renamed Gran Colombia - which would go on to become the name of the eventual state, while Peru retained the same name. Both Colombian and Peruvian rulers could not come in term over the disputed territories of Maynas, Jáen, Guayaquil and the political landscape of infant Bolivia. This quickly deteriorated into a bloody one year war where both failed to solve the problem. Luckily, a key agreement guaranteed peace in 1829, but Colombia lost more than won; it lost influence in Bolivia as well as most of the disputed territories, save for Guayaquil. Gran Colombia was then plundered into a string of crisis, leading to the collapse of the nation and the establishment of two new entities: Venezuela and Ecuador. Gran Colombia renamed itself the old name of the colonial master but functioned as a republic, before finally recovering the post-independence name in 1863.

| Anti-Peruvian poster demonstrating soldiers of Gran Colombia fighting against the run away Peruvian troops. |

Still, Peru's old conflict with Colombia was not solved, nor even with one of its successors, Ecuador. Though Colombian-Ecuadorian relations hadn't been easy since Ecuador became a nation in 1830, Bogotá silently backed Quito against Lima when it came to the border. Frustrated, the Peruvian government could not afford a war with Colombia once more, so it drove attention south toward Chile. By this time, Peru and Colombia followed two distinctly different political systems: Peru changed government and ideologies many times, while Colombia committed itself as a democracy even when Colombia functioned more like a pseudo-banana republic.

In 1879, tensions with Chile blew Peru into a full-blown conflict, and to the shock of many, Chile won the war, destroyed most of Peru, occupying Tacna and Arica as well as widespread looting in Lima and rural Peru. Colombian press celebrated the win of Chile, a desirable feeling after losing too much in the past to the Peruvians, echoing potential reconquest of Amazon basin, which had been laid claim by the Colombians and Ecuadorians. To make it worse, a year after the war with Peru, Chile dispatched warships to defend Colombia over American involvement in Panama, still not an independent state, and rising Chilean-Colombian cooperation. Nonetheless, Colombia defused tensions with Peru.

Peru was stabilised only in 1890s and 1900s, by then the country had endured chaos and massacres of minorities, notably against the Chinese. Peru entered a new era as an "Aristocratic Republic" since being governed entirely by the elites till 1930s. Meanwhile, Colombia struggled to keep democracy afloat, due to weak central governments where Conservatives and Liberals constantly fighting each other. This, in turn, saw Bogotá conceded Panama to the Americans, this time the United States agreed to pay a large sum to make Panama an independent state. Desperate, Colombia and Peru both looked back at the mirror and rebuilt official ties.

Once Colombia and Peru recovered their bilateral and commercial links, sympathies between the two nations grew, as both endured rife and corrupt governments. However, when the relations between Colombia and Peru were growing peacefully, sudden hostilities broke out over the Amazon basin regarding Leticia in 1932 almost threatened to ruin the tie.

|

| A Colombian poster mobilising for war against Peru in 1932. |

| Peruvians protested against the transferring of Leticia to Colombia. |

The war broke out because of Leticia's status in the dispute of 1802 protocol. The Colombians interpreted Maynas, when given to become part of Peru Viceroyalty, didn't include Leticia. The Peruvians interpreted it differently, claiming Maynas, Leticia and the area surrounding Putumayo were incorporated into Peru by the Spaniards. Leticia was the extension of the old hostility over the unsettled Colombian-Peruvian conflict a century ago. The Salomón-Lozano Treaty of 1922, named after Fabio Lozano Torrijos (chief negotiator of Colombia) and Alberto Salomón (chief negotiator of Peru) did little to quell tensions, it dissatisfied the Peruvians for giving Leticia to Colombia.

Once Peru and Colombia failed to negotiate, the dictator of Peru, the Malagasy Luis Miguel Sánchez Cerro issued troops to occupy Leticia. It sparked outrage across Colombia and activated casus belli, beginning a one-year war to finalise the border. The war eventually ended with the assassination of the Peruvian dictator and the finalisation of the 1922 treaty in Brazil. It also marked the end of their early statehood consolidation.

Struggle for peace

Once Peru and Colombia stopped fighting, the duo found itself in a dire need to create stable governments. This meant the two countries realised better having good neighbours than having enemies.

One act that demonstrated the comradeship between Peru and Colombia was the 1936 Summer Olympics scandal in Germany. Peruvian national football team played the quarter-finals against Austria (two years later annexed to Nazi Germany) and won the match 4-2, but an orchestrated pitch invasion and military march in Berlin led the Peruvians accused of instigating violence in the field, which the Peruvian defence was never heard and the match had to be rearranged. Angered, the Peruvian Olympic delegation left Germany distraught. The Colombian delegation, informed about the news, joined the protest and left Germany. It was believed that Adolf Hitler and the Nazi officials had some role, with Joseph Goebbels, the Minister of Propaganda for Nazi Germany, was the mastermind.

Colombian solidarity with Peru helped to heal the wound of 1932-33 war greatly and these two became strategically close. Their closeness was not unfounded, given its instabilities ripping both nations apart. The duo then issued declarations of war against Nazi Germany in 1943 and 1945. Still, Colombia and Peru had engulfed in a dispute over Peruvian politician Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre finding sanctuary in Colombia. The two countries had a bitter confrontation, which later ended with a diplomatic victory for Lima, although exchanged by the freedom of de la Torre not to be curtailed.

Peru and Colombia have been later thrown into states of turmoil since 1940s.

In Peru, long before Haya de la Torre sought asylum in Colombia, together with José Carlos Mariátegui, a Basque mestizo communist, both two wrestled for power from 1920s. Mariátegui was a well-educated columnist and thinker who shaped Peruvian politics, while Haya de la Torre was a radical left-wing populist who founded the American Popular Revolutionary Alliance, or APRA, known in Peru as the Aprista Party, stands as the oldest political party in Peru. Mariátegui died young, at the age of 35 in the capital Lima, but his thought survived and transformed into major Latin American political thoughts, the Basque advocated for structural reforms from depth. Haya de la Torre was more like a revolutionary thinker than the Basque mestizo, but he had the debt from him, once elected President of Peru.

|

| Victor Raúl Haya de la Torre (1895-1979), who would go on to shape Peruvian politics for five decades. |

Sadly, the Peruvian Armed Forces viewed de la Torre with suspicion, thus never allowed him to take the oath. Luis Miguel Sánchez Cerro persecuted him and tried to establish an authoritarian government. Óscar Benavides, another military marshal came to Presidency, did nothing to improve the conditions, violently suppressed the APRA before resigned in 1939. Manuel Odría overthrew the government in 1948 of moderate José Bustamante y Rivero because of the perceived President's weaknesses against APRA. Odría was a tinpot corrupt leader, came down hard to APRA before gave power to Manuel Prado y Ugarteche (already served as President under Benavides's power transfer until 1945). Just like Bustamante y Rivero, Prado also had difficulties communicating with APRA. Haya de la Torre had to enter an alliance with Odría, but the government of Prado was toppled in 1962 and Fernando Terry became President.

Juan Velasco Alvarado, a left-wing dictator, created a left-wing junta by toppling the Terry Administration in 1968. APRA was banned by Velasco as well. Nonetheless, APRA stood up against Velasco's nepotism and radical leftist reforms by recruiting some of its most promising members, one being Alan García, the future Peruvian President for two terms, and became a symbol of hope against either left or right-wing dictatorships. Velasco almost prepared a war against Chile in 1975 but was toppled by Francisco Morales Bermúdez, who would reverse many of Velasco's leftist policies. Morales Bermúdez was more tolerant than any former junta leaders of Peru, and APRA was finally recognised, at last, as an official political party of Peru. It was too late, though, and with ailing health, Haya de la Torre finalised the 1979 Constitution, his last act, on his deathbed.

Haya de la Torre's death triggered a wave of national mourning but also paved way for the rise of a bloody insurgency second only to the Colombian conflict in 1980s. The old Communist Party was gone and replaced by a more radical Maoist Shining Path (Sendero Luminoso). Many were admirers of Haya de la Torre even though they clashed with him in many of the ideologies. Thanks to illicit drug trades, Sendero Luminoso went on to become one of the deadliest militant groups in Latin America. The other group, Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement (MRTA - Movimiento Revolucionario Túpac Amaru), named after the last Inca ruler, was more traditional to the Soviet orthodoxy. MRTA and Shining Path were hostile to each other and frequently fought in numerous conflicts. Shining Path proved to be stronger and exceeded with far deadlier attacks, causing the Peruvian authorities to take actions. But Belaúnde Terry and Alan García failed to deliver the promise, and the crisis, coupled with economic mismanagement and natural disasters, tainted the country.

|

| Poster of Sendero Luminoso. |

What made the Shining Path so deadly was its Maoist teachings. The founder, Abimael Guzmán, also known as Chairman Gonzalo, visited China in 1960s and was influenced deeply by Mao Zedong's people war. A college teacher before visiting China, Abimael was known as the shampoo, since he could inspire and wash a person's head. When Abimael waged the war, China had already had a different leader with a reform mindset. No matter. He moved forward with the plan and even recruited young girls to his ranks (over 40-50%). Because of women's presence, it caused serious troubles for the central government. Bombings and massacres became commons in areas controlled by Sendero Luminoso.

Because of the violent nature of the Maoist group, Rondas Campesinas - autonomous peasant armies - were set up to fight the Shining Path. Received military hardware and training from the United States as parts of anti-communist wars, the Rondas proved more effective than the central government and even became private paramilitaries, often turned blind by Lima for the same goal. That said, it was not until 1990s that Peru entered a new era under a President-turned dictator, the Nikkei (Japanese overseas) Alberto Fujimori, who beat the novelist Mario Vargas Llosa in 1990 election.

A deeply anti-communist by person, Fujimori despised the Peruvian legislative system for what he perceived as ineffective to fight the communists, staging the autogolpe (auto-coup) in 1992, suspended the constitution and rewrote it to enhance the President's wing or Fujimorists.

Once the problem solved, Fujimori ensured American support and increasingly used the paramilitaries Rondas, as well as the state Intelligence Service, to launch reprisals against Sendero Luminoso. Fujimori also introduced Fujishock to recover the country's economy, which was successful but exacerbated inequality in the country. Fujimori's handling against Sendero Luminoso also got him the credit and in 1995, he won the second term. Fearing that the ground would lose, Abimael speeded up the plan by a string of bombings, most notably the Tarata Apartment bombing in July 1992. Two months later, Abimael was arrested and imprisoned for life, and the group splintered. MRTA militants also took part, taking hostages at the Japanese embassy in December 1996. President Fujimori saw this as an attack on his ancestor country Japan, and responded heavily, killing 14 hostage-takers. Widespread corruption and human rights violation under Fujimori regime did little to change the President's power grasp, until 2000 when the scandal (called Vladi-video) by Vladimiro Montesinos, head to the Intelligence Service, bribing politicians to favour Fujimori, led to his collapse. But ten years under the Nikkei President was enough to shape modern Peruvian politics, which would be found in the new millennia. By this time, however, the military no longer involved in Peruvian politics.

In Colombia, by 1900s, the political landscape in the country was very abnormal. It had the oldest democratic commitment in Latin America, but ran like a banana republic. Well, the term "banana republic" was coined by American writer O. Henry in 1904, but this came after he witnessed a string of violence in Honduras and various Latin American states exploited by America's United Fruit Company. And Colombia perfectly suited the category.

Colombia had suffered a bloody civil war called Thousand Days' War lasted from 1899 to 1902, killing nearly 150 thousand people. The United States mediated to end the fight, but the situation had not improved much. Partisan factions emerged under either the Conservatives or Liberals, many only wanted to get a cake for their own interests. The Conservatives held power in early 20th century before losing to the Liberals from 1930s to 1940s, which began the transition of the economy to a wealthier state after the devastating crisis from 1928 to 1933.

The Conservatives were not happy, though, they became fearful that the Liberals were leaning toward communism, thus tried to wrestle for power once more. Mariano Ospina Pérez finally beat the Liberals in 1946 to restore Conservative power. Yet one man changed the whole nation forever.

Jorge Eliecer Gaitán was a charismatic member of the Liberal Party and he was running to become President of Colombia. Everyone rallied behind him and he was about to win the candidacy and possibly the Presidency. Gaitán was popular because he was exposed to the poverty of the people outside the capital Bogotá, he shared solidarity and pain with them, giving an oratory for his followers. He was the former Education Minister and an attorney, which further enhanced his popularity.

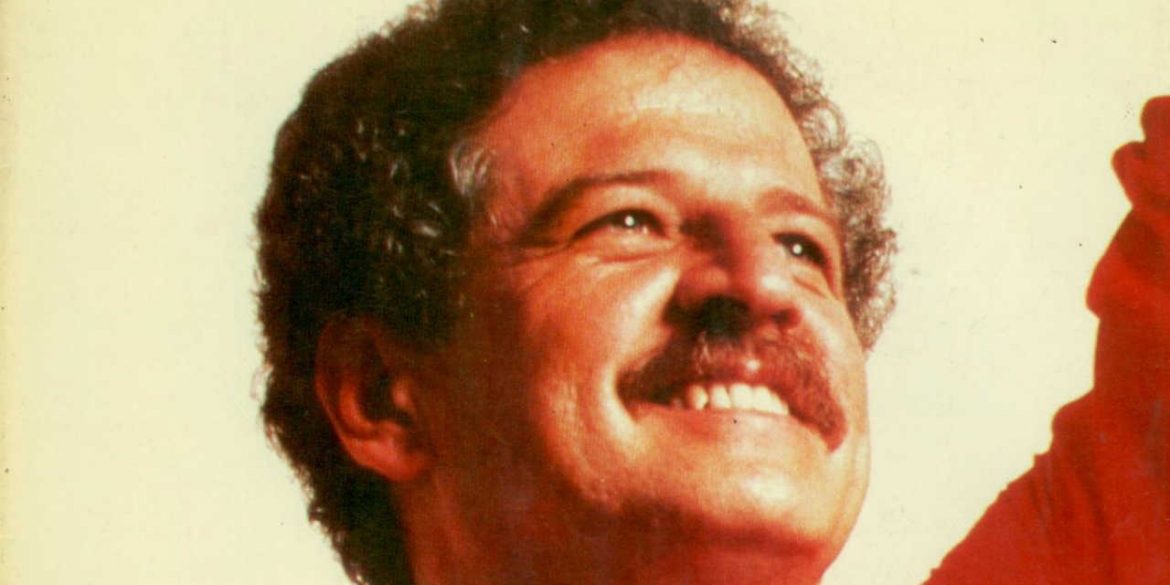

|

| Jorge Eliecer Gaitán addressing his supporters, 1946. |

Eliecer Gaitán would not live up to run for President, however. On April 9th 1948, he was assassinated by an unstable and jobless man named Juan Roa Serra, though this theory remained in dispute due to Roa Serra's difficulties in communication and his lack of gunning skills; many claimed that Roa Serra was framed and the real gunner had escaped from the scene (the mystery still unresolved today). Too late, many Colombians were outraged by the murder, rioted across the capital in an incident known as Bogotazo - which the future Cuban communist leader, Fidel Castro, took part in.

|

| The Bogotazo of April 1948. |

The unrest lasted for ten hours, killing 1,000. Gaitán's death sparked unrest, but it was the start. Negotiations between Conservative leadership and Liberal opposition failed to materialise, and war broke out. The negotiations initially included a joint anti-communist front, but Pres. Ospina Pérez framed the Liberals as communists and tortured many of them. The police and military sided with the Conservatives, so was the Catholic Church. The peasants and middle-class sided with the Liberals. Colombia was split. An attempt to murder Ospina Pérez was launched in November 1949 but was called off, except one: Air Force Captain Alfredo Silva proceeded it violently, joined with Eliseo Velásquez, a peasant guerrilla leader. It also failed when the Conservatives were quick to retaliate.

The escalation and widespread uprising didn't deter the Conservatives. Laureano Gómez, another Conservative, came to power in 1950 after accusation of electoral fraud and pogroms against Liberal politicians. Laureano Administration was ineffective in dealing with the rising death tolls and casualties despite his anti-communism, and thus he was removed by Colonel Gustavo Rojas Pinilla in 1953, creating a four-year junta rule. Pinilla blamed the previous Administration of ineffectiveness, escalated the violence by banning the Communist Party and persecuting politicians of Liberal wing.

Finally, the traditional elites of both Liberal and Conservative Parties reached an agreement in 1957 to form a united National Front to end the civil war. This led to the deposing of Gustavo Pinilla and futile attempts to heal the two warring factions. The National Front would soon be regarded as authoritarian due to systematic election rigging and the Constitution of 1886 which the losing political party be given adequate and equitable participation in the government, and was replaced back into a unitary republic in 1974. Still, the creation of the National Front marked the end of a bloody civil war known by today's historians as La Violencia (The Violence).

Unfortunately, the issues left behind by La Violencia only began to surface.

Various leftist militant groups, dissatisfied with the sharing power agreement between Liberals and Conservatives of 1957, refused to buckle. One man, Manuel Marulanda Vélez, in the jungle, founded the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC - Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia) in 1964. They became the oldest guerrilla army in Latin America. Another group, the National Liberation Army (ELN - Ejército de Liberación Nacional), also came to existence the same year, by Fabio Vásquez Castaño, who returned from Cuba. The M-19 army, named after the April 19th Movement (Movimento 19 Abril), founded in 1970 after former dictator Gustavo Rojas Pinilla lost the election. They had spent a decade travelling between Russia and Vietnam to receive military training before finally waged total wars against the government.

|

| FARC fighters, somewhere in 1980s or 1990s. |

What made it different from Sendero Luminoso/Shining Path in neighbouring Peru was the embracement of Marxist-Leninist ideology. These fighters, be it FARC, ELN or M-19, considered revolutionary the highest cause of Colombian struggle, though FARC was far more relevant. The ability of the FARC leaders also proved to be highly recommended, as they could convince large number of people to join the ranks. Clumsy methods by the Colombian government, many wrongly believed FARC would be defeated so easily, didn't curtail its powers, rather expanded it. President Julio César Turbay was condemned for being passive while Belisario Betancur signed a peace treaty with FARC lasted only three years (1984-87).

The problem didn't end here. A man who actived in illegal good smuggling, Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria, received a man who fled from Pinochet's Chile, a drug smuggler and producer. The Chilean man introduced the drug making technique and his cocaine lab in Peruvian Amazon, ultimately resulted in Pablo Escobar becoming one of the wealthiest and most violent drug lords in the world. Quick to adapt, Pablo Escobar enriched himself by making drugs, notably cocaine, and his income increased dramatically. Notably, he made drugs now a key tool of his empire. He also managed to disguise his face immediately, pouring billions of dollars to build facilities for the poor in Medellín, the city where he grew up. Pablo Escobar eventually got elected into the Colombian Congress, but fate encountered him to Rodrigo Lara, a very faithful lawyer and attorney who fought against drug trade. In just a day entering the Parliament, he was expelled immediately by Lara, then the Minister of Justice. Deep grievances let Pablo to order the killing of the attorney, and so the situation escalated.

Escobar expanded his empire despite government's efforts to curtail his trade, notably one factor: he was able to recruit a lot of Peruvians into his networks. It was necessary to mention that, even when Escobar had henchmen from Venezuela, Mexico, Panama, Bolivia, Ecuador, Chile, El Salvador, Honduras, Cuba and Brazil, the Peruvians still played a significant role. Just like in Colombia, Peru had been under constant instabilities, many impoverished Peruvians trying to find their new life often ended up working with Escobar's associates. Escobar didn't regard his Peruvian underlings highly, but important to keep them long enough because Peru is the largest cocaine plantation in Latin America, offered the highest quality.

This suited Escobar dearly. Colombia had been under crisis, but only worsened from late 1980s, and Escobar's drug empire coexisted alongside many warring factions turning Colombia into a war zone. The city of Medellín, where he formed the Cartel, was referred as the most dangerous city in the world. Assassinations against opponent groups and police became normality, the state of fear lived throughout Colombia. FARC, though not always have close relations with Escobar, benefited from the Kingpin and accelerated its activities against the government, even brutal bombings. Throughout 1980s to 1990s, U.S. governments had long feared Colombia would be a failed state.

Yet one man decided to fight back in Colombia: the President César Gaviria.

Gaviria was initially not going to become President of Colombia, he was just a secretary for another Presidential candidate, Luis Carlos Galán, for 1990 Presidential campaign. Galán had a lot of similarities with the late Jorge Gaitán in 1948 - he was charismatic, popular, member of the Liberal Party with strong determination to make judicial and political reforms, Minister of Education for some time. Of course, assassination too.

When Galán greeted his supporters in Soacha, Cundinamarca, on August 18th 1989, he was shot dead. Galán's support for an extradition treaty with the United States, his vehement anti-cartel campaigns and political corruption were thought to have triggered the response from Escobar and various traditional Liberal politicians. His death caught the country to a full mourning, while the United States received this with shock, President George H. W. Bush even referred the death of Galán with sorrow.

|

| Luis Carlos Galán. |

Gaviria was at Galán's funeral, when his family members called for the people to rally behind Gaviria, nominated him as candidate for Colombian Presidency. Shocked, Gaviria reluctantly accepted the role. Lucky for Gaviria, another attempt to assassinate him went on missing the target. Escobar ordered to detonate a bomb in the Avianca Flight 203 bound to Cali. Gaviria was supposed to take the flight, but a warning from DEA (Drug Enforcement Agency) agents forced him to halt the flight. It saved him when 107 people on board were killed. Gaviria's miraculous survival enabled his popularity to reach the peak, became the 28th President of Colombia.

Gaviria's task as President was difficult. He had to rebuild the country's already collapsing economy while the same time trying to remove guerrilla factions and drug cartels. Gaviria didn't have the charisma of Galán, but he still tried the best, even by going as far as claiming that this would be his only Presidential term. Over four years, Gaviria aged, but he finally had his achievements: Pablo Escobar's crime syndicate was disbanded in 1993, following the killing to the Kingpin. Gaviria also succeeded in reducing areas of FARC and other guerrilla forces, with helps from the paramilitaries. He also enabled the 1991 Constitution which enabled Colombia to become a full-fledged democracy despite flaws. When Ernesto Samper took the chair in 1995, violence however re-escalated after Escobar's death. People accused Samper of conspiring with leftist militias and the Cali Cartel, the only drug cartel in Colombia after the collapse of Escobar's - resulting Samper being condemned. Later, it was found he got involved in a scandal with the Cali cartel on the process to become Colombia's 29th President. Thing changed little under the 30th President Andrés Pastrana.

In 2002, a new President was elected in Colombia. This man was no other than Álvaro Uribe. One thing characterised Uribe was his nearly identical political view to Peru's Alberto Fujimori. Like Fujimori, Uribe had been sceptical of the Parliament's ineffectiveness, so he tried to change the constitution and consolidated power to create political mechanism that favour his wing - similar to what Fujimori did, except Fujimori had to make an auto-coup to achieve that goal and refurbished the mass, while Uribe only added his elements into the 1991 Constitution. Then, both fought leftist guerrilla groups and achieved successes against Shining Path and FARC, often with the helps of the paramilitaries. Moreover, Fujimori and Uribe were capable of having the United States on their side. Fujimori and Uribe were also politically right-wing and fiercely pro-capitalism and pro-economy, often made platforms to encourage strong neoliberal rhetorics - in the end they succeeded in reorienting both nations to global economy and economic growth at unprecedented level, but followed with greater disparity of wealth and high unemployment rates. Finally, human rights - something both Fujimori and Uribe had low regard with - both governments had shown no mercy in killing people, regardless who they're.

This situation would become a legacy, a legacy that hard to abandon even if you dislike him.

Overcome or not overcome?

Protests in Peru and Colombia recent years show that people in both are tired with the establishment. But the scenes behind reveal it won't be simple.

An important character to understand Fujimori and Uribe is their shadow power weighing from behind so huge and so apparant in the societies. In Peru, despite Fujimori had resigned from Presidency in 2000 (later extradited to Peru from Chile in 2008 for trial), Fujimoritas stay powerful enough to challenge political reforms. Later Presidents: Alejandro Toledo, Alan García, Ollanta Humala and Pedro Kuczynski had to appeal the elites (mostly pro-Fujimori) in order to survive power scare. In Colombia, the same situation occurred when President Juan Manuel Santos could not convince hardliners belong to Uribe circle about the FARC peace deal and social policies, he left office with low approval.

Alone in Peru, the political crisis occurred in 2017 has not come to an end. Fujimori's children, Keiko and Kenji, have been active in political surface and controversies with regard to the Fujimoristas only further deepen divisions. One President, Alan García, ended his life on April 17th, 2019 after being framed for corruption over Brazilian conglomerate Odebrecht scandal. Manuel Merino, a protégé of Alberto Fujimori, only came to Presidency for two weeks, but himself also involved in order to bring Alberto's daughter Keiko to power. Meanwhile, scandals in Peru don't stop with Odebrecht, but widened to even COVID-19 vaccine controversy, the cartel-like system manipulating Peruvian politics and hostilities between centrist-rightists to leftists, with the Fujimoristas always have hands in the final decisions, usually in favour of the rights against the lefts. Many Peruvians had demanded total overhaul of the political system of Peru.

The same crisis in Colombia that broke out since 2019 applies for the similar situation. Many Colombians accused Iván Duque, a protégé of Álvaro Uribe, of undermining judicial system and mass murders against unarmed civilians, this became bigger in 2021. Yet polarised political process in Colombia makes reforms difficult because Uribe still has supporters, a lot. Uribe wants neoliberalism to remain in charge, like the Fujimoristas, and believe that an integral joint police-military system would handle everything. So do the elites of Colombia, gaining power in a system known as "parapolitics" as many of them were originally right-wing warlords. Colombia is also entangled with the corruption case of Odebrecht as well, causing people like Juan Manuel Santos to be placed under question. Many modern Colombian politicians on Uribe's circle are still being seen as having ties with drug cartels. The police and military have been on the side of the government because they made revenues with support from the elites. Colombians, like Peruvians, are yelding for changes.

It has the positive outcome, though. Not everything is under the dark moon.

The people of Peru and Colombia come to also realise, that, they're not alone in their fights. There is a inter-border solidarity developed between Peruvians and Colombians. The protest in Peru had received strong Colombian youth backing. Now, young Peruvians are sending passions to Colombia. The sense of love and respect is getting stronger and proves critical.

Yet, unless there is a radical reorganisation of these nations' governments, it's going to be difficult. In the case of Chile for instance, the country had to endure for over 50 years to finally herald for changes after being reeled by widespread protests against Pinochet-era institutions, which eventually sparked the Latin American Spring to Peru and Colombia. Meanwhile, governments of Peru and Colombia have been historically less stable than that of Chile, so the cost could be even more ruinous if the oppositions failed to figure how to run their states. Think how Peru struggled for democracy, think how Colombian democracy is just a farce.

Colombia and Peru are having their own tragedies, different yet inter-connected... No one knows what's next...

Comments

Post a Comment